Neetu Sharma, Jyotsna Sripada and Shruthi Raman

April 10, 2023

Hunger and Malnutrition in India after a Decade of the National Food Security Act, 2013

What is the status of hunger and malnutrition in India?

The year 2023 marks a decade since the enactment of the National Food Security Act (NFSA) 2013. In translating the right to food into a legal entitlement, the NFSA is a milestone in the history of food security legislation in India. The Act aims to provide food and nutritional security through a life cycle approach by ensuring access to adequate quantities of quality food at affordable prices, to enable people to live with dignity. However, despite 10 years of food security being a legal right and the availability of sufficient quantities of food grains, India has at least 189 million (nearly 19 crore) people—14% of its population—suffering from serious hunger. India ranks 107th out of 121 countries in the Global Hunger Index released on October 14, 2022, placing it in the ‘serious’ category for the 22nd consecutive year. The fundamental and unanswered question is: why do so many people in the country face persistent hunger and vulnerability for generations?

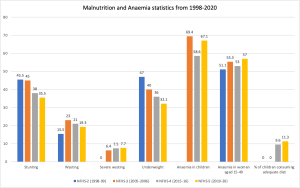

India’s hunger and malnutrition statistics are particularly worrying when it comes to children and women. The country is off track with respect to five of six targets for maternal, infant and young children nutrition, which address stunting, wasting, anaemia, low birth weight and childhood obesity, as per the last Global Nutrition Report, 2021. Since the Family Health Survey, 2015-16 (NFHS-4) and NFHS-5, 2019-21, the incidence of anaemia has increased by 1.8 percentage points among pregnant women, by 3.9 percentage points among all women in the reproductive age, and by 5 percentage points among adolescent girls. Among children, the increase is the highest—at 8.5 percentage points. The current overall figure is closer to that in 2005-06, when the prevalence of anaemia was 70%. Progress in tackling this has been slower than expected, with the pandemic knocking down whatever little could be achieved through a wide spectrum of interventions including the National Nutrition Mission, or POSHAN Abhiyaan.

Why is the NFSA, 2013, not sufficient?

The enactment of the NFSA signalled a shift from a ‘welfare to rights-based approach’ to food security. It set up a legal framework for benefits under existing programmes like the Targeted Public Distribution System (TPDS), Mid Day Meal Scheme (MDMS), Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) and maternity cash entitlement. The Act established a monitoring mechanism and a grievance redressal mechanism. For the first time, hot cooked mid-day meals for school-going children, cooked meals and take home rations for children under 6 years of age, pregnant and lactating mothers, 5 kilograms of food grains at highly subsidised prices for 50% of urban and 75% of rural population and cash benefits for pregnant and lactating women became justiciable legal entitlements. The internal grievance redressal mechanism mandated the implementing departments to have helplines, call centres and complaint boxes. Independent mechanisms include the designation or the appointment of District Grievance Redressal Officers (DGROs) and State Food Commissions (SFCs) at the state level.

The persistence of high levels of hunger and malnutrition in the country despite a comprehensive law may be explained partially by the inadequacies inherent in the law and the dilutions that have marred its implementation. NFSA fell short in recognising the need for a diversified food basket and other such strategies suggested in the National Nutrition Policy, 1993. It also failed to recognise the legal entitlements accumulated through a number of interim orders and continuous mandamus by the Supreme Court of India in PUCL Vs Union of India.

In the spirit of a life cycle approach, NFSA offered a range of entitlements but limited itself to the distribution of food while subjecting critical production issues involving agriculture and farmers’ welfare to progressive realisation. Even in terms of provisioning, NFSA entitlements were less than the benefits already being extended by many state governments. In such cases, NFSA often proved to be detrimental—for instance, the withdrawal of the Anna Bhagya Scheme in Karnataka—which demonstrates either the inability or demotivation of state governments to protect pre-NFSA benefits.

NFSA covers up to 75% of India’s rural population and 50% of its urban population. Its substantial coverage—considering the poverty levels in the country—is posed as a counter-argument when questions are raised about the manner of estimating beneficiaries. This estimation has been based on 2011 Census figures rather than updated population projections. State governments have had to navigate an intriguing upside-down formula to determine the criteria for identifying beneficiaries based on prescribed numbers, rather than based on predetermined criteria. A few state governments have had to make multiple revisions to their identification criteria to arrive at the magic numbers prescribed by the central government.

During the initial years of its enactment, state governments grappled with the overlapping provisions of NFSA and TPDS Control Orders issued under the Essential Commodities Act 1955. Initial confusion over where to retain provisions related to ration cards, fair price shops and monitoring & grievance redressal for TPDS—TPDS Orders or NFSA State Rules—led to delays in the framing of NFSA State Rules. In most states, including Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Rajasthan, comprehensive Rules have not been formulated till date, leading to incongruous implementation. On many aspects, such as social audits, the role of vigilance committees and local authorities, no Rules have been framed or notified by most states.

Are adequate resources being allocated?

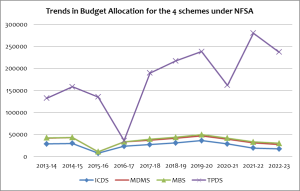

An analysis of budget allocations for the four schemes under NFSA so far reveals no identifiable trend. Allocations have been on a declining trend for the Integrated Child Development Services, and on an increasing trend for the Maternity Benefit Scheme. No change can be attributed to the budget allocated for the Mid-Day Meal Scheme.

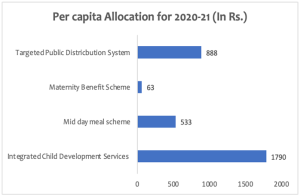

The per capita allocation—calculated on the basis of population projections released by Census of India, 2019—is not sufficient to ensure food security for rights holders. For instance, the amount available for a child in the age group of 0 to 6 years is INR 1,790 for a year. This is grossly insufficient when it comes to preventing malnutrition or diseases caused by it. The situation is dire in the case of school-going children, for whom the per capita allocation is INR 523 per year. This reflects the paucity of nutritious meals being provided in schools, which affects the nutritional and food security of children. The amount available under the Maternity Benefit Scheme is only INR 63, which is not even close to the INR 6,000 ensured under the Act.

One possible solution is to lay impetus on the inclusion of locally grown foods in service delivery systems, which will reduce the burden on the Union Government as well as ensure food and nutrition security of rights holders.

Despite the limitations of NFSA, state governments could optimise its provisions through proactive measures, especially by framing effective State Rules and allocating adequate budgets for implementation. The substantial coverage under NFSA offers an opportunity to address widespread hunger and malnutrition. Every year NFSA facilitates food and nutrition support to about 92 crore individuals, including 9.06 crore children below 6 years of age, and pregnant and lactating mothers; about 11.8 crore school-going children, and about 82 crore people who should have access to TPDS. Maternity cash entitlements reached about 2.5 crore women in the year 2020. Sections 31 (1) and 31(2) of the NFSA further provide abundant opportunities for states to provide benefits over and above NFSA entitlements to ensure that the right to food and nutrition can be realised by everyone. Progressive and comprehensive rules, combined with enhanced budgetary allocations, are key to optimising the potential of NFSA in safeguarding food security in India.

About the Authors

Dr Neetu Sharma is the Coordinator & Programme Head at the Centre for Child and the Law, National Law School of India University, Bengaluru. Ms Jyotsna Sripada is a Research Associate at the Centre, while Ms Shruthi Raman is a Project Coordinator. They can be reached at .