Madhur Bharatiya

August 30, 2024

Uttar Pradesh Prohibition of Unlawful Conversion of Religion (Amendment) Bill, 2024: A Short Commentary

On 30 July 2024, the Uttar Pradesh State Assembly passed the Uttar Pradesh Unlawful Conversion of Religion (Amendment) Bill, 2024 (hereafter referred to as ‘the Bill’). This will become law once it receives the approval of the Governor. The ‘Statement of Objects and Reasons’ of the Bill invokes the protection of the dignity and social status of women, and points to alleged activities of foreign and ‘anti-national’ elements and organisations leading to unlawful religious conversion and demographic change. These developments, it is argued, necessitate a stronger anti-conversion law to replace the Uttar Pradesh Prohibition of Unlawful Religious Conversion Act, 2021 (hereafter referred to as ‘the Act’).

Some of the key amendments proposed in the Bill include more stringent penalties for existing offences, new categories of offences, crucial changes regarding who can file an FIR, and the introduction of a procedure for obtaining bail. This commentary examines the provisions of the Bill in light of contemporary social, political and legal developments, and finds that stricter punishments within a vaguely framed legislation leave scope for potential misuse of the law, and make religious minorities more vulnerable.

Background: When rumours govern law-making

In 1977, the Supreme Court upheld the validity of anti-conversion laws passed by the states of Madhya Pradesh and Orissa, which paved the way for other states to pass laws governing religious conversion.[1] Over the decades, the constitutional validity of several of these state legislations has been challenged before the Supreme Court on various grounds. Observers have raised concerns about the interference of these laws with the right to privacy, the right to practise and propagate religion promised by Article 25 of the Constitution, and other fundamental rights. It has been argued that some of their provisions have the ‘effect of creating an absolute prohibition on interfaith marriages which entail a prior or subsequent adoption of another faith’. Anti-conversion laws have also been reported to violate international norms.

Legislations regulating conversions also need to be seen in the context of data questioning the necessity of such laws, existing documentation on their potential for misuse, and research on the nature of prosecution and procedural lapses in such cases. Several reports point to the persecution of religious minorities carried out under the pretext of curbing unlawful conversion (see instances here and here).

Nevertheless, there seems to be an eagerness among states to introduce anti-conversion laws,[2] or to make existing laws more stringent—as in the present case. This raises several questions. What are the bases for the enactment of these laws? What is the kind of evidence that informs their formulation? Is the stated intent behind their enactment—preventing ‘forced’ conversions and demographic change—based on facts or misleading claims?

Proposed amendments to penalties

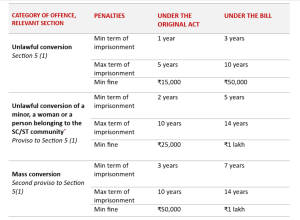

The Bill proposes stricter punishments for acts of unlawful religious conversion. This is based on the rationale that existing penal provisions under the Act are ‘not sufficient to prevent and control religious and mass conversion of certain protected categories of people’. Harsher punishments for activities such as mass conversion are likely to affect cases involving voluntary conversions to escape caste discrimination. The table below presents the penalties under the original Act alongside those proposed under the Bill.

Table: A comparison of penalties prescribed under the existing Act and the new Bill

* Note: The Bill adds the category of ‘disabled or mentally handicapped person’ to the list of persons whose conversion would constitute an aggravated offence—existing categories include minor, woman or person belonging to a Scheduled Caste or Scheduled Tribe.

Source: Author, based on the original Act and the proposed Bill.

The Bill introduces two new categories of aggravated offences. First, it penalises the receipt of money from any ‘foreign or illegal institution’. The punishment prescribed for this offence is a minimum of seven years and a maximum of fourteen years, along with a fine of ₹10 lakh.

This amendment begs the question of reasonableness when it comes to curbing alleged unlawful conversions. The phrase ‘foreign or illegal institution’ has not been explained in the Bill, making any kind of foreign funding susceptible to being interpreted as funding from an ‘illegal institution’. This potentially amounts to a blanket prohibition of foreign funding, even when such funding may have been legally obtained. This provision also needs to be read in the context of amendments made to the Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Act in the year 2020, which have been criticised for adversely impacting the functioning of NGOs and other human rights organisations. Such developments raise several questions about the process of investigation and prosecution, which often unfold following clickbait headlines or social media posts vilifying, among others, minority-run charitable organisations.

The second new category of offences deals with the intention to convert by (i) putting any person in fear of their life or property; (ii) assault or use of force; (iii) marrying or promising to marry or causing inducement or conspiring towards it; (iv) inducement for the purpose of trafficking a minor, woman or any person or for otherwise selling them, or attempting or conspiring to do so.[3] The Bill prescribes 10 years’ rigorous imprisonment for these offences, extendable up to life imprisonment. This is in addition to a fine, to be recovered from the person accused, of the amount required to meet the medical expenses and rehabilitation of the victim. Compensation of up to ₹5 lakh payable to the victim must also be recovered from the person accused.

Even as the Bill proposes to raise the maximum punishment for these offences to life imprisonment, nowhere does it explain how the ‘intention to convert’ will be determined. The vague wording of this provision is especially worrying given its potential impact on voluntary conversions carried out for the purpose of marriage.

Vague provisions and stringent bail conditions

Article 25 of the Constitution places restrictions on the exercise of the right to profess, practice and propagate religion to public order, morality and health. The Statement of Objects and Reasons of the proposed amendment goes beyond these threefold restrictions and cites the alleged involvement of ‘anti-national’ elements, a vague umbrella term devoid of any sound legal reasoning, to introduce stringent bail conditions.

Under the original legislation, the offences committed under the Act are non-bailable. However, the amendment prescribes a stringent procedure to obtain bail, subject to the fulfilment of three requirements. (i) The Public Prosecutor must be given the opportunity to oppose the bail application. (ii) The Sessions Court must be satisfied that no offence has been committed by the person accused under the Act. (iii) The Sessions Court must be satisfied that the accused is not likely to commit any offence while on bail.

The third requirement is a well-settled judicial principle governing the law on bail. The first two requirements, however, are the same as the stringent bail provisions prescribed under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002, and similar to those prescribed under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967, Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985, and state legislations such as the Maharashtra Control of Organised Crimes Act, 1999.

Recent developments, such as the deployment of the Anti-Terrorist Squad to investigate alleged offences under the existing anti-conversion Act (see instances here and here) deepen the perceived association between religious conversion and ‘anti-national’ activity. Oral observations by the apex court invoking national security in the context of conversions, allude to loosely defined illegalities. Vague definitions and stringent bail conditions are common features under anti-terror laws, and their inclusion in the Act are a cause of concern.

Who can file a complaint? Lessons from the scheme of laws governing domestic relationships

The broad scheme of laws governing marriage give protection—and thereby the locus to initiate legal action—only to an ‘aggrieved person’. For instance, Section 198 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (Section 219 of the BNSS) permits only the aggrieved person to file a complaint for offences against marriage such as bigamy, barring under certain circumstances.

While Section 4 of the original Act states that only an ‘aggrieved person’ or their relative by blood, marriage or adoption, can file an FIR with respect to acts of unlawful conversion (defined in Section 3), the Bill proposes a significant amendment: ‘any person’ can file an FIR for an offence under Section 3. In the context of marriages and relationships in the nature of marriages, this effectively brings in an outsider within the domain of a legislation that seeks to regulate such relationships, raising concerns on the right to privacy of the concerned parties. While the inclusion of family members already made consensual inter-faith or inter-caste relationships susceptible to criminal complaints filed by disgruntled family members—often under the influence of vigilante groups—the inclusion of ‘any person’ in the Bill legitimises the direct involvement of vigilante groups or anyone who objects to an act of religious conversion.

Crucially, the Bill deepens the criminalisation of religious conversion. A persistent critique of special laws governing marriage, or issues incidental to marriage, is that they are unable to address social problems without pushing couples in consensual relationships—in certain cases, involving young adults—into the purview of criminalisation without justification. A similar trend can be observed in the application of anti-conversion laws, with instances of interfaith couples in live-in relationships seeking protection from the courts, only to be denied the same.

Overall, the Bill reflects how the very act of religious conversion is increasingly being seen from a broad and homogenised lens of suspicion. The proposed amendments, based on unverified rhetorical claims (‘anti-national’ elements, demographic change, etc.), not only undermine the process of law making, but are likely to create a chilling effect on the exercise of a fundamental right. Stricter punishments, accompanied by vague language and features of counterterror legislations are likely to make already vulnerable individuals, minority communities and minority institutions, even more vulnerable.

Notes

[1] At present, 12 Indian states have anti-conversion laws: Arunachal Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Gujarat, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Jharkhand, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Rajasthan, Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh.

[2] This can be inferred from an affidavit filed by the Rajasthan Government before the Supreme Court in a petition seeking action against alleged mass conversions, expressing its intention to introduce an anti-conversion law.

[3] The text of this provision in the Amendment Bill in Hindi is lacking in clarity, and therefore, a clearer analysis of this provision will be possible once the official English translation is made available.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Professor Sarasu Esther Thomas for her inputs, and Nishtha Vadehra for her edits.

About the author

Madhur Bharatiya is a Research Associate at the Centre for Women and the Law, NLSIU.