Reflections on the ‘Indian Political Thought’ Conference

January 28, 2025

The National Law School of India University, Bengaluru (NLSIU) organised a three-day interdisciplinary conference that delved into Indian Political Thought (IPT) from January 8 to 10, 2025. The conference aimed to explore the historical foundations of Indian political thought, assess their contemporary relevance, and envision future trajectories. Renowned scholars, researchers, and practitioners participated in critical discussions to analyse the dynamics, intersections, and evolving contours of Indian political thought and practice, offering fresh perspectives and valuable insights.

Conveners

Prof. Shruti Kapila (University of Cambridge) and Dr. Karthick Ram Manoharan (NLSIU)

Schedule

The conference kicked off with a keynote address by Prof. Madhavan K. Palat at BIC on January 8, followed by panel discussions at the NLSIU campus on January 9 and 10.

The Keynote Address

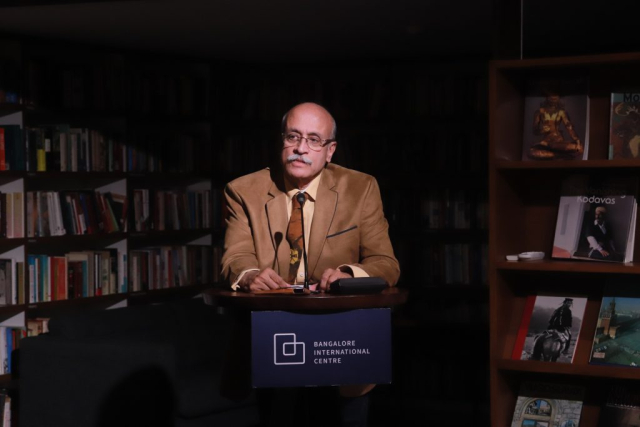

Topic: “Nehru’s Democracy”

Speaker: Prof. Madhavan K. Palat

Nehru presented himself as liberal and socialist; and while he did not declare himself to be a conservative, he readily deployed Burkean and traditionalist arguments for the legitimation of Indian democracy. But he also warned repeatedly that democracy could destroy itself through a democratic dictatorship and the tyranny of the majority. He derived the sources of democracy from the panchayats of tradition and from the nationalist traditions from the 19th century, and he asserted that it had become the yugadharma after Independence. He always argued that democracy had to be a movement that was dynamic but with institutions that were stable. When these came into conflict, as they inevitably must, he chose movement over institutions. The movement emerged from nationalist mobilization, and the institutions from the Constituent Assembly and its Constitution. He never ceased to warn that the Constitution was not a sacred text and that democracy could be protected only by democracy, not by the Constitution. As such, he repudiated in effect any concept of a Basic Structure. He sought to extend parliamentary democracy through Panchayati Raj, reasoning that democracy must be broadly based like a pyramid lest it topple. But ambiguities stalked him. He looked upon panchayats as bureaucratic as much as democratic extensions; he was dismayed that the electoral system was run ever more by knaves and scoundrels rather than visionaries like himself; and he feared that democracy was breeding an elective aristocracy and oligarchy. While he was unhappy that the two-party system did not seem to be evolving in India, he presciently discerned that India was run by a two-ideology system of Congress and Hindutva which could, at some time in the future, become parties. He saw the vital need for a moral ideal, but his idols were Buddha, Ashoka, Akbar, and Mahatma Gandhi, none of them democrats except for Gandhi, who was confessedly autocratic while engaging in a democratic mobilization. The only consistently democratic ideal he could present was himself, but he found a personality cult vulgar and comic. He despised democracy as promoting the average and the dull, but he feared that inspiration, charisma, and lofty commitment seemed to lead into politics of the right, which he deplored. His politics consisted in reconciling contradictions of this sort and living with ambiguities and inconsistencies, preferring the pragmatism of the conservative to the theoretical clarity of the socialist.

Watch the Keynote Address

Panels and Panelists

The conference hosted six panels over January 9 and 10, 2025, with renowned scholars, researchers, and practitioners, participating in discussion on topics such as ‘law’, ‘authority’, ‘visions of geopolitics’, ‘liberalism’, ‘caste’, and ‘religion/secularism’.

View the details on the panels for the main sessions.

Reflections from the speakers

Prof. Madhavan K. Palat

Indian Historian

“It was greatly stimulating and educative to participate in this conference on Indian political thought which embraced the concepts and domains of law and the constitution, authority and power, geopolitics, liberalism, caste, religion and communalism, and thinkers as varied as those in the tradition of nitishastra, and Tagore, Gandhi, Lohia, Nehru, Ambedkar, Dicey, Kelsen, and Schmitt. I was privileged to deliver the keynote address on Nehru’s Democracy and to hear the many critical responses to the lecture. I cannot think of a better place in which to hear such a range of ideas and to test my own.”

Prof. Faisal Devji

Professor of Indian History

Director, Asian Studies Centre

Fellow, St Antony’s College

University of Oxford

“The conference on Indian political thought at NLSIU was a stimulating event at which a number of very original arguments were broached. It was an honour to participate in the discussion with my paper on the varying fortunes of civil war and revolution as crucial categories of the political imagination in India and the world.”

Rajeev Bhargava

Director, Institute of Indian Thought

Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS)

“Thanks for a very stimulating workshop. It was unusual not only for the range of issues it covered but because it lasted just the right time. Not a single session seemed over-extended or boring. The organizers provided an opportunity for the participants to be flexible and the latter responded by being reasonably self-disciplined. There was enough time to present and discuss. All in all, congratulations to the organizers for getting the right kind and the right number of scholars who gelled well to make the outcome productive and meaningful.”

Dr. Salmoli Choudhuri

Assistant Professor of Law

Affiliated Faculty, M.K. Nambyar Memorial Chair

NLSIU

“Introducing political thought in Indian law school is a fresh initiative and holds immense promise for revolutionizing both fields, particularly by making legal studies more philosophical. The conference, therefore, is a decisive step in the right direction. I am thrilled to have had the opportunity to discuss Tagore’s ideas of freedom, which illuminate important aspects of liberalism and law in the twentieth century.”